I returned from a brief trip away this week, and when I least expected it a visit to an art gallery taught me something profound about the nature of art, what writing can be, and how publishing is an industry that values breadth rather than depth, to its detriment. I was also moved, almost to tears, by twenty bales of hay and some T-shirts.

This piece is for my reader-supporters only, though I will make it free to all in two months’ time. Going forward, almost all of my Compendia posts will be for my reader-supporters, but to reflect this change I have reduced the price to the minimum Substack will allow. I’m humbly asking you to support me so that my work can continue, and in return I promise I’ll continue to send you interesting and informative posts like this one, posts that the traditional publishing world would never let you see.

I went on holiday. Those that know me will be picking their jaws up from the floor right about now, as that’s not something I do very often.

It’s not that I don’t like holidays, it’s just that I never get round to organising them. I overthink them, I tell myself I’ll wait until my diary is a bit freer, or I’ve finished a particular piece of work. I forget that my diary has its own momentum, and tends towards the same level of busy/not-busy unless I actually do something to keep space free. I also forget that not only does the work I tend to have a very loosely defined ‘finish’ point, but that there’s always, always something else stacked up on the runway waiting to take flight. Add to that the fact that I will sometimes travel for work (which I kid myself is a holiday), and that even when I’m travelling for not-work I still take work with me ‘just in case’, and you can see that I have to make a concerted, and determined, effort to create time away from home where the primary focus isn’t writing or reading, or talking about writing, or feeling guilty for not reading.

But anyway, recently I managed it. A number of things came together to make me realise that I needed to move further, and faster, towards embracing spontaneity, curiosity and playfulness, both in my work and personal life. (More on that soon, and you’ll be seeing some changes in this Substack). The stars aligned, something I’d been planning to do was cancelled, freeing up diary time, and a friend mentioned that they were going away and asked if I fancied joining them. So, I booked flights, and a hotel, and a week later was on my way to Copenhagen.

I worked on the flight out there, but only because I wanted to (and yes, that’s the great thing about my work. Sometimes — not always by ANY means, but sometimes — it doesn’t feel like work at all), but not once I’d got there. I just focussed on, y’know, having fun and relaxing and eating a bit too much food and drinking a bit too much beer.

On my last day, my flight was late in the day, and check-out time midday. My friend was busy, but that was okay. When I travel I like to spend a bit of time wandering alone — I take my camera and do some street photography or just chill out in coffee shops — and this time I decided I’d go look at some art, with a visit to Copenhagen’s SMK Museum (Statens Museum for Kunst).

I was initially drawn there because they had an exhibition of Alberto Giacometti’s work and, though I’m not particularly familiar with his art, I’ve always been intrigued by it. So I had a wander round there, and to my surprise enjoyed the pictures as much as the sculptures.

I saw other stuff, too. And, almost more importantly, there were rooms I didn’t even go in. I’m not a fan of paintings that look realistic (and neither am I knowledgable enough about art to be able to give that type of work its proper name). I can appreciate the enormous talent and artistry, of course, but with a few exceptions the work just tends to leave me cold. I can sit for hours, literally, in front of a Rothko, but will walk past a Monet with barely a second glance.

Similarly, Giacometti’s spindly, stick-like figures move me in a way that something that might be a more ‘accurate’ representation of the human form — Michelangelo’s David, say — does not.

There’s no adult in the room ready to tut loudly because I don’t give a crap about the Canalettos.

This is not to dismiss those pieces of art, or to shade anyone who might love them but hate Rothko’s ‘blobs of colour that anyone can do’. We all like different things, after all. I’m no expert, and it’s probably a massive oversimplification, but I suppose there was more of a place for those accurate, representative works in the days before photography. Now, if we want to record what something merely looks like, we can take its image. So art moves on, it’s now about capturing some other thing, something deeper, more resonant. It’s about saying something about the thing it’s representing rather than just, y’know, representing it.

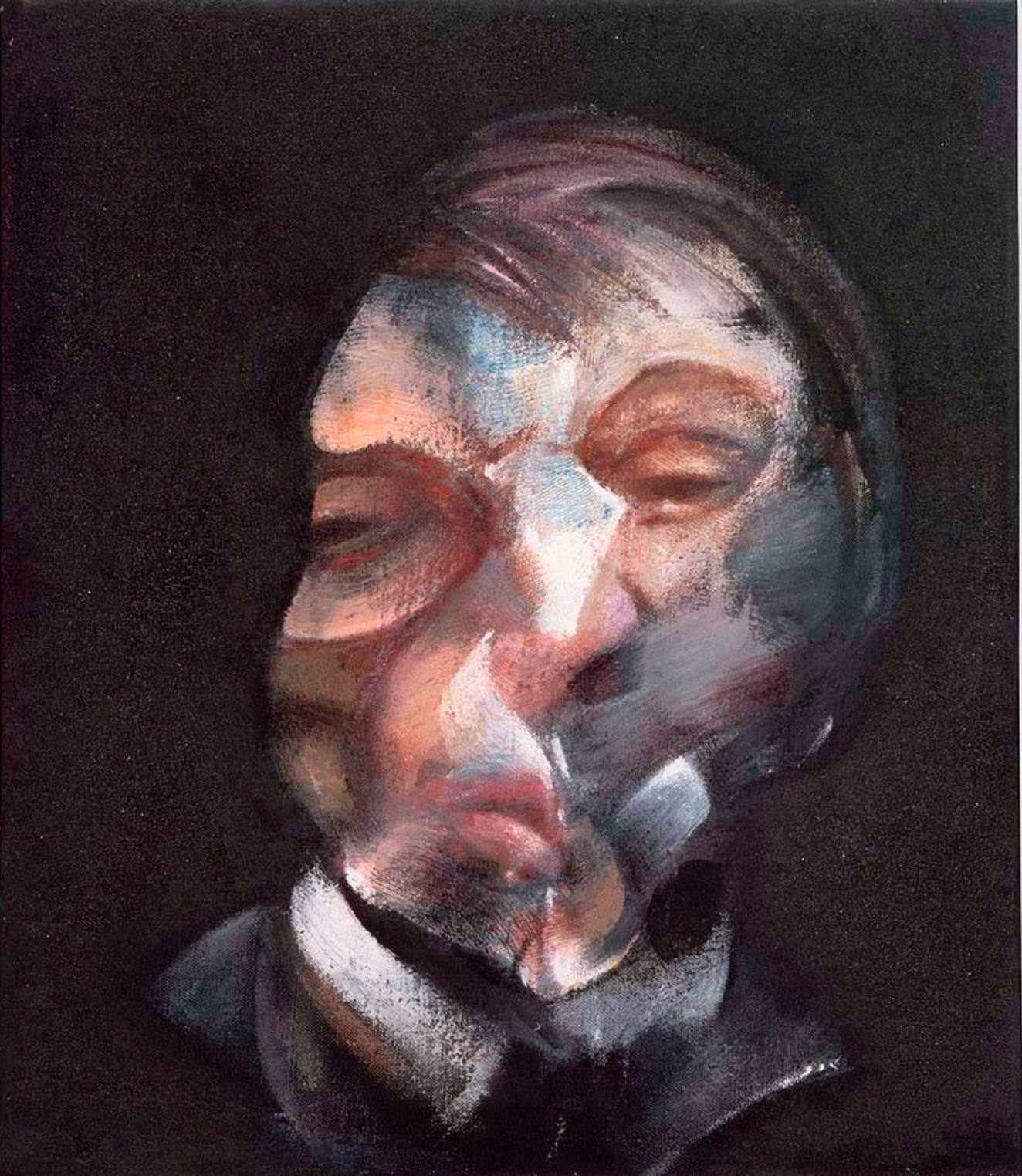

Take this self-portrait by my favourite artist, Francis Bacon. Is that what Bacon looked like? No. But that matters not. We have plenty of photos of him, if that’s what we want to see. But this picture, presumably, captures his essence, or at least the way he saw himself when he painted it. And to my mind that’s far more interesting.

But each to their own. And that’s the great thing about about visiting museums as an adult. I don’t have to traipse around the place, looking at pictures I don’t like, trying to feel something. I can head straight to the stuff that sings to me, there’s no adult in the room ready to tut loudly because I don’t give a crap about the Canalettos. For me, art now should be about making you feel something, rather than merely representing life. if it doesn’t, walk on.

But does the same thing apply to writing? One could argue that the work I’ve done so far, most books in fact, are representative. They tell a story. He went there, she did that. This happened, then that happened. Some do it with more flair than others. Some authors are particular about the words used to tell the story, they intend to evoke layers of meaning, or provoke emotions or feelings in addition to the surface story. But there’s still a limited palette, a framework provided by the structure of ‘story’ and the rules of grammar and punctuation. Some, I guess, go for the Francis Bacon or Giacometti approach — a sort of multi-layered, multi-dimensional representation, but how to go for something more like the Rothko, where the meaning is buried and open to wild interpretation, while also writing something that people will actually read?

It’s a tricky one, and I don’t pretend to have answers. There are people who are playful with language, who experiment. Jeanette Winterson, perhaps, certainly in some of her earlier work. Max Porter. They’re getting there, I think. But it’s not easy, and once someone has been labelled a commercial writer, a genre writer, the industry doesn’t want it. They want illustration, candy-floss. They don’t want art.

Anyway, these were the thoughts in my head as I wandered the galleries of SMK. And then I saw this.

I confess I almost walked right past it. I mean. It’s not much to look at, I thought. It smelt, a bit, it was clearly real hay. Some hay with some clothes. Big deal. How pretentious.

But — a bit like Emin’s bed is just a bed until you put it in the context of the time when she created it, that it’s actually about someone having a breakdown — I realised this was not, could not be, a piece of art that was purely to be appreciated for how it looks. So I read the description on the wall.

I learned this. ‘The hay was cut on one of the largest mass graves in north-western Bosnia and Herzegovina, where massive ethnic cleansing took place in the early 1990s. The clothes on the drying rack formerly belonged to victims who tragically ended their lives in the mass graves.’

I stopped breathing for a moment. Suddenly this was a powerful piece, capable of making the viewer reflect on death, on war, on the transitory nature of life and even of rebirth (the hay has been fertilised by the decaying bodies of the victims of ethnic cleansing, after all). A piece capable of cutting to the very heart of a genocide. It’s powerful, profound stuff. Much more than the sum of its parts. Would you want it in your living room? No, but that’s no longer the point of art. Maybe it never was.

And maybe writing — especially fiction — can be more than the sum of its parts, too. I walked into the room containing ‘Cleaning Times’ with no knowledge and no expectations but, because I did have curiosity and an open-mind, I left profoundly moved, almost shaken. And a story can do that too. If we enter into it with the right spirit, and engage with it empathetically, then fiction can be profoundly moving. When it’s allowed to be.

Over to you!

What books have moved you? What authors have you read that are stretching the boundaries of what writing can be?

Our views on art differ - I prefer pictures that actually look like what they're supposed to be. But I totally agree with you on the hat bales. I would have instantly dismissed it as 'not art' but when you know the story behind it, it becomes something immensely powerful.

The most most powerful novel I've ever read is Mr Two Bombs by William Cole - about a man who survives both the Hiroshima and the Nagasaki atomic bombs. Little known but I'll never forget it.

‘When it’s allowed to be.’

BULLET!